THIS IS A DRAFT

Hiya, this is a draft! Probably never going to finish it at this rate.

TODO

- prune images that aren't needed.

- Add pictures of tree's being traversed!!!

- StackOverflow posts:

- https://stackoverflow.com/questions/31323283/incomplete-traversal-using-link-inversion-of-binary-tree

- https://stackoverflow.com/questions/22288074/robson-tree-traversal-algorithm

Introduction

In this post, we will discuss a novel tree traversal algorithm. The standard traversal method operates with a linear spatial cost. The Robson traversal counters with a cool constant space!

The final code is on github↪ , but I encourage you to read this post! The table of contents may help for people that may want to skip a bit :)

Table of Contents

TODO

The Famous Tree

The tree is an incredibly important data structure. A great learning tool for beginning computer scientists, starting to understand the science. Trees are also used throughout the real-world. File systems use B-trees↪ to store their data↪ . Text editors use ropes↪ to organize their text↪ . Trees power the world, inside and outside of computers. We will be using a simple binary tree for this post.

Here is a common binary tree definition. We will be using C for the whole of this post:

/* We will use this type definition later. */

typedef void (*VisitFunc)(Tree*);

typedef struct Tree {

int data;

struct Tree* left;

struct Tree* right;

} Tree;

We can use the tree like so:

int main(void) {

Tree root, root_left;

root_left.data = 0;

root_left.left = NULL;

root_left.right = NULL;

root.data = 1;

root.left = &root_left;

root.right = NULL;

}

We will specifically be using Binary Search Trees↪ , so that way in-order traversal works.

How Do We Traverse a tree?

Traversing a tree means accessing each node's data in the whole tree. This is obviously a critically important function of a tree, we should be able to access all elements if we need to.

Luckily, traversing a tree is super easy!

void traverse(Tree* cur) {

if (cur == NULL) return;

pre_visit(cur); /* pre-order traversal */

traverse(cur->left);

in_visit(cur); /* in-order traversal */

traverse(cur->right);

post_visit(cur); /* post-order traversal */

}

This algorithm is universally taught in beginning CS courses at universities. It gets the job done, but I think we can do better.

Tree traversals can be adapted for use in memory management. Many garbage collectors represent their memory pool using tree-like structures, and when they are marking live memory, they traverse that tree.

Pre-order traversal always visits a parent before its child. This is very useful

when you want to copy a tree, maintaining its order. In-order is mostly used for

sorted trees, as it will visit nodes in order! A node will be visited in post-order

only after its children have been visited. This means that post-order is best used

for tasks such as deleting the tree, freeing its memory without dangling pointers left over.

If we made free our pre-visit function, then we would never be able to traverse right children!

Why is the 'standard' method bad?

To get into how algorithms are rated against eachother, we need to talk about "Big-O notation", and that is a little bit out of scope for this already long blog-post, so... Take an algorithms course I guess? I'll give a quick paragraph.

Big-O uses a polynomial to describe how the function performs with relation to input size.

If we are talking about speed, an O(n) function will perform linearly with regards to input.

An O(1) function will always perform the same no matter how big the input gets. You should try

to avoid O(n!) functions, too... These functions are used for 'time' and 'space'. If you

are interested in this stuff, please check out

CLRS↪

chapter 3 for more information, or ask me to write a post on it!

The 'standard' traversal method is as efficient as possible, time-wise.

We need to traverse all n-nodes of a tree, and the algorithm has O(n)

run-time complexity. You cant get any better than that!

A reader may think that you also cant get better space-wise.

The algorithm is like 4 lines long, how can we get better than that!?

Well, if you paid attention in (or had taken an) algorithms class,

you would know that stack space counts! Even though this algorithm

looks small and perfect, it uses up a whole stack-frame each time the algorithm recurses!

If you turn this recursive code into an iterative, explicit-stack based, solution,

you would see that you need some memory for each level, and in the worst-case,

we need O(n) memory!

You may be saying now, "O(n) is not that bad! It seems as good as it can get!" Well I say no! We can do better! I say we can do it in constant O(1) time!

That means we can do it using the same amount of memory, no matter how big the tree gets!

Let's do it!

How can we do better than that!?!?!

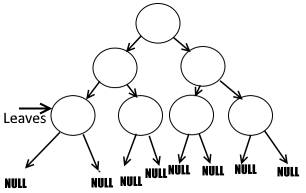

Here is the thing about trees: they can be quite wasteful!

Let's look at a tree-structure:

You see, the leaf-nodes have 2 pointers that are just null!

What a waste! Thats so much space we are wasting! For any given tree of n nodes,

there will be n + 1 null pointers.

Here is the theory. We use that freely-available space for our traversal. That way, we use as little extra memory as possible!

That is how we are going to get to our solution, but first we need to understand some preliminary concepts.

Stackless Traversals

As mentioned in the introductory sections, the standard tree traversal requries a stack to traverse the tree. This is becuase we need to 'pop' back up the tree once we reach a leaf. Using a stack is super easy to understand, and it makes for a clean algorithm.

explain stack for a minute here or in the big-O section. Chef says, at least explain a 'pop'.

In 1968, Donald Knuth asked the computer science community if there existed a method for computing tree traversals without a stack, while also leaving the tree unmodified. Lets discuss some methods for doing just that, ending in the Robson traversal.

The Link-Inversion Model

Link Inversion is a key ingredient to our final algorithm. Link-Inversion is a process where we use a marker-bit on each node to tell if we should continue to traverse up, or traverse rightward when going up a tree.

This method is stackless, like in the threaded tree, and solves Knuth's question. It does not solve our dilemma though, we need O(1) worst-case space complexity! Lets talk about how and why it works, which will lead us to Robson.

typedef struct Tree {

int data;

Tree* left;

Tree* right;

bool went_right;

} Tree;

void link_inversion(Tree* cur, VisitFunc pre_order,

VisitFunc in_order,

VisitFunc post_order) {

Tree* prev = NULL;

Tree* old_prev;

Tree* old_prev_left;

Tree* old_cur;

if (cur == NULL) return;

do {

/* 1) Descend leftward as much as possible. */

while (cur != NULL) {

pre_order(cur);

cur->went_right = false;

old_cur = cur;

cur = old_cur->left;

old_cur->left = prev;

prev = old_cur;

}

/* 2) ascend from right as much as we can. */

while (prev != NULL && prev->went_right) {

old_prev = prev;

prev = prev->right;

old_prev->right = cur;

cur = old_prev;

post_order(cur);

}

/* 3)

If prev is null after coming back up from the right,

it means that we have finished traversal,

so head back to the while-condition and get outta here!

Else, we will do an exchange here,

swap to right child of parent. */

if (prev != NULL) {

/* Switch from the left side of prev to the right

Also, mark prev as went_right so we know to traverse

upwards using right pointer. */

in_order(prev);

old_prev_left = prev->left;

prev->went_right = true;

prev->left = cur;

cur = prev->right;

prev->right = old_prev_left;

}

} while (prev != NULL);

}

The core algorithm is in the name, we must invert the links. As we push down the tree, we invert the links so that way the child points to the parent, and we can walk up the tree the same way we walked down. As we go up, we need to un-invert the links so that way the tree is back as it started. The marker bit is used so that when we go back up, we know if we are ascending from the left or from the right.

Lets talk about each of these steps.

-

We must start by traversing leftwards as much as possible. Keeping pointers to the current and previously visited nodes. As we traverse, we invert the links. That means that cur->left will be changed to point to the parent.

-

Next may not make sense, so if it doesnt make perfect sense, come to it after step 3. Here, we are done with this subtree, so we want to get to the subtree's root. We do this by ascending from the right until we get to the root of the traversed part of the tree. This ensures the tree is in a state that step 3 can deal with.

-

Thirdly, we do an exchange. Here, we are assuredly in a left child, thanks to step 2. We can safely traverse to the parents right child and forget completely about the previous subtree forever! This exchange marks a completion of the left subtree of the new root, now we must traverse the right subtree of the new root. Back to step 1!

Here, we are skipping some of the technicalities, like what is went_right for?

It is so that we know when we get to the end of the subtree in step 2.

Hopefully, I will elucidate why its necessary with pictures very soon.

After I elucidate that, I will later explain why it's not necessary (hint: Robson!).

Walk-through

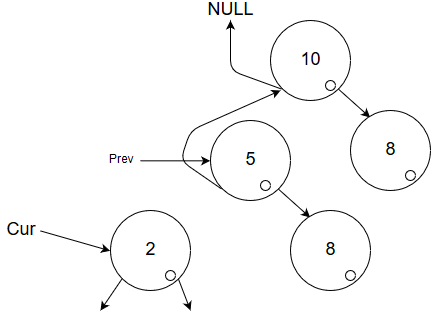

The algorithm is weird, but I think it'll help by showing it!

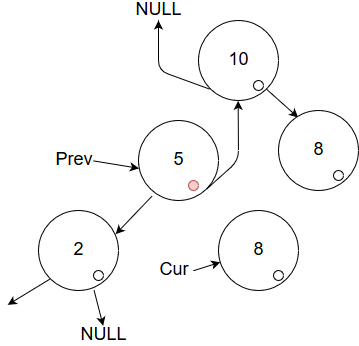

Here, the tree has been traversed almost completely down the side. Each time we step downwards, we invert the links to point to the parent. The next step will be to venture into the NULL left-child from the current point.

This image has not even finished the first run of step 1 from above yet, so lets continue.

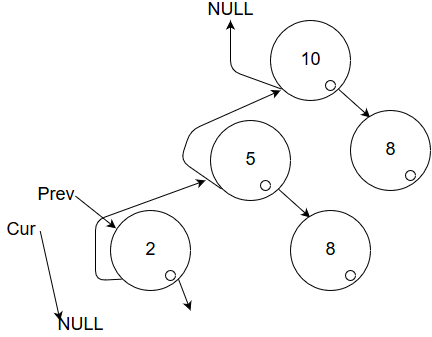

Okay, we have successfully finished part 1 of the algorithm: 'go leftward a lot'!

Now step 2 does not apply, went_right has been set for exactly 0 nodes at this point in execution.

We swiftly move to step 3! Here, we perform an exchange.

We have finished traversing the left child of the current subtree (the leaf), and now we must traverse the left.

We do some swaps and end up here:

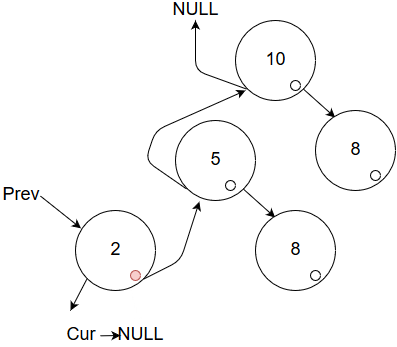

Okay, the exchange succeeded! We are back at step 1, because prev != NULL.

Lets ignore the red circle for just a moment and execute step 1.

Done! Did you see it? Nothing!

Of course, cur == NULL, so step 1 is not run. Time for step 2! We must go up until we reach the root!

We run this until prev->went_right == false, in this case one time.

Running this step means we are prepared to forget about the current subtree.

Step 3 will exchange once more, getting us to the parents right child:

If you are keen, you may have noticed that this is a strikingly similar image to the first one in the series.

The only difference is the red marker in the prev node. If you apply the operations I have listed since the

start of this subsection, you can fully traverse this tree. Making enough images to illustrate all of that

is an exercise left to the reader.

Link inversion is relatively complex when compared to the standard method, but definitely more fun!

Warning

This algorithm is dangerous! If you attempt to modify the tree while it is being traversed, pointers will be a complete mess! Make sure this algorithm completes before altering the tree any more!

Analysis

- Space-Complexity:

O(n)- This is because each tree node needs a marker, so linear cost.

- Time complexity:

O(n)

We still have not yet improved on the algorithmic cost of the standard depth-first search. We have been doing quite well on solving Knuth's challenge, but thats only a minor goal! Lets get to the real thing now, the Robson traversal.

The Threaded Tree

J. H. Morris presented the threaded tree in 1979, and it involves using those wasteful null nodes at the ends of the tree. However, you will see it does not solve all of our problems.

Threaded trees have two bits, one for each direction, telling whether the pointer is a thread.

If the left pointer is a thread (cur->left_thread), then cur->left points to the in-order

predecessor. The same is true for cur->right_thread pointing to the in-order successor.

Following threads is a constant operation to the predecessor/successor, which speeds up in-order

traversals.

typedef struct Tree {

int data;

struct Tree* left;

struct Tree* right;

bool left_thread;

bool right_thread;

} Tree;

/* Takes the root of the tree (we call it cur for readability in the function itself) */

void threaded_traversal(Tree* cur) {

/* Go all the way down to the smallest number in the tree. */

while (!cur->is_thread) {

cur = cur->left;

}

/* Now all we have to do is go rightwards until the end! */

while (cur != NULL) {

inorder_visit(cur);

cur = tree_successor(cur);

}

}

/* Returns a successor to any given node, `node`.*/

Tree* tree_successor(Tree* node) {

Tree* cur;

/* fast path! */

if (node->right_thread) return node->right;

/* else return leftmost child of right subtree! */

cur = node->right;

while (!cur->left_thread) {

cur = cur->left;

}

return cur;

}

This Tree struct includes a boolean field to tell whether the current tree node has an in-order thread.

When we search for the in-order successor to the current node, and find that it is a thread, we take the

right node to get the immediate successor! This is always a single operation, AKA O(1) time!

You note, of course, that to support this method, we need to add a boolean field for each and every node in the tree! This means we are stuck with a linear space cost for this traversal.

Threaded trees are super cool, and I would love for people to know them. Luckily, there is a great Wikipedia page↪ on the subject. If there was not, I would definitely write more.

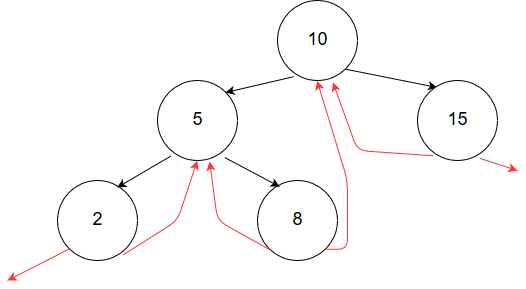

I won't do a full walkthrough of the threaded traversal, but here is an image of a threaded tree:

To start, go to the leftmost node, which is the minimum of an inorder traversal. To find the successor, if the right pointer is a thread, follow it, and that is the successor. If it is not, take it, and then go left as much as possible, that is the next node in-order.

Analysis

- Space-Complexity:

O(n)- This is because each tree node needs 2 markers, so linear cost

- Time complexity:

O(n) - Time complexity for finding a single successor: Amortized

O(1)!- Ask for that algorithmic analysis post if you want me to explain this!

So we have found a cool algorithm that makes use of those dumb null pointers at the fringes of the tree. It does not seem like we gain much, though, as it still comes at a linear spatial cost. If you want amortized constant successor finding, then this is a great algorithm for you!

The Robson Tree Traversal

Here we are! The Robson Tree Traversal is a method for traversing trees in linear time, and in constant space.

Robson learns from the threaded and link-inversion models. By using the leaf-pointers as pseudo marker-bits, we create an awesome tree-traversal.

The downside of the threaded-tree was that it is linear-space. Yet, it successfully used those null pointers that we lamented of their waste. The downside of the link-inversion model is that it is worst-case linear-space. We had to add an extra bit of memory to each node. Robson solves both problems by playing to the strength's of both!

The Algorithm

Lets start by talking about the memory usage. We need a few bytes of memory for this to work, here is what we will be using those bytes for:

- a

curpointer. This will be the current node that we are algorithmizing. - a

parentpointer. Fairly self explanatory, we need to know the parent of the current node at any given time. This does not need to be part of the data structure, we will just update our single pointer as the algorithm runs. - a pointer we call

available. This will be used to point to a node that we can use in our 'leaf-stack', that I will describe later. - A pointer called

top. This will be the top of the aforementioned and still mysterious leaf-stack. - a temporary pointer used for exchanging nodes similarly to link-inversion.

- a bool used to keep some state regarding how we have been traversing the tree.

These variables are kept in the function, and other than them, the only memory needed is the tree itself! Unlike the other algorithms mentioned in this post, this tree is completely basic. There are no changes to the underlying data structure from what you learn in CS102. Now, lets move to the algorithm itself. The core algorithm is split into two parts: pushing down the tree, and finding the next subtree.

First, we push down the tree while inverting the pointers, a la link-inversion. We go down the tree not until we hit the left-most node, like in link-inversion, but when we hit a fully fledged leaf. The inversions themselves are a bit different than in link-inversion. There are a few couple to consider:

- There is a left child. Here, we follow the the left child. The left pointer is set to the parent of the current node, and the right is unaltered. This follows link-inversion, nothing to change here.

- There is no left child, but there is a right child. Here we do the same as case 1, but we set the current right pointer to the parent. This is very important, we leave the left child's pointer alone as null. When we go back up the tree, we will see that the parent's left is null, and know that we are ascending via the right tree. This is important in preserving the tree's structure.

- There are no children (as in cur is a leaf). This is the start of the interesting stuff! Robson uses the leaf nodes as a sort of pseudo-stack. The leaf-stack tells us where to ascend from when we dont know if we are ascending from left or right. Here, we simply will track the leaf as 'available'. Wow! We are at a leaf! That means it's time to go up!

Lets discuss these states with pictures! If someone wants to write an interactive javascript demo of this, be my guest!

Going up the tree, we have 4 cases, some mundane, and some interesting!

- The parent's right pointer is null. Here, we must be ascending from the left. We un-invert the pointers, as in link-inversion. No funny business yet!

- The parent's left pointer is null. This is a mirror of the previous case, so ascend using the right pointers instead of the left.

- Now, the tree has both pointers, how do we know if we are ascending from the left or right? Here we are getting a bit interesting! We are at an 'exchange point', where we do not know if we should ascend from the left or from the right. Lets move out of this list and talk about the leaf stack, and its relation to exchange points.

The Leaf Stack

The leaf stack is not a real stack, but a linked list, composed of tree leaves.

The right pointer of each leaf/stack-element points to an 'exchange point'.

Each left pointer points to the next element of the list/stack.

We call it a stack because we only access the top element, and therefore it is treated as a stack.

Also, its a cheeky 'im not touching you' to Knuth's challenge. Anyways, these exchange points are used

to tell if we are ascending from the left or right. Lets get back into the cases!

The available pointer's destiny is to be the new head of the leaf-stack.

Before we add it to the stack though, we must find an exchange point.

I'll leave the answer for not immediately adding it to the stack as an exercise to the reader.

Once we find an exchange point we will set available to the head of the leaf-stack.

Okay! Now lets get back to finding the next subtree to traverse!

TODO: does this last sentence need more reasons/usage? I feel like people will get caught up on what an exchange point is, and lose grasp of the section.

- Back at the old #3, we were discussing what to do when the parent has both children. Let's discuss the more difficult and more fun case here. When `top` is null, or when `top->right` does not point to the parent, we know we are ascending from the left. This is what we refer to as the exchange point, where the leaf stack first comes into play! We will use `available` now and then go down the right subtree. We set `available->right` to the parent, `available->left` to `top`, and then `top` to `available`. Woohoo, its a linked list! After these shenanigans, there are more shenanigans! We can not fix the pointers as in link inversion, as `parent->left` is currently pointing to `parent`'s parent! What we will do is set `parent->right` to `cur`, and `cur` to `parent->right`! It looks funky when you draw it out, but it works! Now we are on an un-traversed section of the tree, so we can resume the go-down part of the algorithm! In the next case, we will make use of the leaf stack!

- Okay! In this final case, we are pushing up the tree, and find that `parent == top->right`! This tells us we are on ascending from the right, and have thus completed the left and right side's of this subtree! Congratulations! Now, we 'pop' off of the leaf-stack, and fix the pointers. Remember how the parents right pointer is pointing to the left child? Yeah, now we re-set that! We set `parent` (the root of the subtree), to `cur` and continue pushing up the stack using the rules I just laid out!

The algorithm really isnt that hard, but when you look at the tree mid-algorithm, it can be really funky. Pointers just completely out of place, but still kind of beautiful in a way! Oh yeah, another reminder to not edit the tree while running this algorithm! The tree is not in a safe, workable, state during these traversals!

Analysis

Amazing.

Conclusion

If anyone knows who JM Robson is please tell me, I've tried searching for him, but to no avail. Also,x if anyone uses this algorithm, please let me know, I'd be super interested to see it used somewhere real.

P.S.

On x86 systems at least, the least-significant bit of a pointer will always be 0, so you could theoretically store anything there, as long as you swap it for 0 when you need to actually use the pointer. So maybe as another way to do this stuff, you can just use one of the pointers' low bits as the follow pointer in link inversion. However, that would be really ugly to code, and then I would have had less to write about :(

relevant discussion↪When not to use robson

Robson only works on binary trees i think(!)

if you need to stop the algorithm at any time the tree will be in a terrible state, you need to run the algorithm completely before doing anything else with the tree.